Months before the ex-president’s death, his daughter shared these memories . . .

What was once my father’s office is now his bedroom. On top of the desk where he rested his elbows as sunlight slanted through the window, where he wrote his last letter to America announcing that he had Alzheimer’s in 1994, bedsheets are often stacked—ready to be used for a change of the hospital bed where he now stays around the clock. When he is awake, which is not that often, he can gaze at the trees outside the window. The other day, my mother and the nurse who was on duty moved the bed to the open doorway so he could look into the back garden, where the sun was making prisms on the leaves after a morning of rain. “Did he seem to notice the different view?” I asked my mother. “I don’t know,” she said.

People often ask me how my father is doing. They want to know if he still recognizes me, if he still recognizes any of us. It makes me realize that my mother and I have been so protective of his condition since he became ill—almost a decade now—that it has allowed people to imagine he is still talking, still walking, still able to stumble into a moment of clarity. But it would be a disservice to every family who has an Alzheimer’s victim in their embrace to say any of that is true, and I don’t believe my father would want us to lie.

Today, we are like many other families who come to the bedside of a loved one and look into eyes that no longer flicker with recognition. It rearranges your universe. It strips away everything but the most important truth: that the soul is alive, even if the mind is faltering.

My father is the only man in the house these days, except for members of his Secret Service detail who occasionally come in. It’s a house of women, now—the nurses, my mother, the housekeepers. Me, when I am there, which is often, since I live only 10 minutes away. When my brother Ron visits from Seattle, or our older brother Michael comes over, the sound of a male voice seems to register with my father. He lifts his eyebrows. Is it recognition of his sons? Curiosity about this new male intruder? I don’t know. We frequently arrange dinner around his bed. In fact, it has become the center of the house. Everything radiates from that space, whether he is awake or asleep. It radiates from the man whose life is thinning to a stream, yet flows and follows us even when we drive off the property.

In the room next to my father’s, my mother now sleeps in a new bed. The king-size bed they shared for so many years came to feel vast and empty to her, so she had it taken away and replaced by a queen-size bed. Less empty space across the mattress. Yet it’s no relief from the loneliness of sleeping alone after 50 years of rolling over to the person you love. She still tiptoes across the floor if she gets up in the middle of the night; her heart forgets that the other side of the bed is empty. I remember the day the larger bed was replaced. I remember the mark on the carpet where the king-size bed once was. It seemed to say everything.

Alzheimer’s is a long series of I-don’t-knows. My father’s doctor doesn’t know how he has lived so long with this disease, especially after breaking his hip in January 2001. I think it’s the tenacity of his soul—he just isn’t ready to leave his reunited family. At a certain point in time, it might all come down to this—life is about learning how to die, how to let go and how to hold on to what is really important. One thing that was so startling about the TV movie that has gotten so much publicity is that it was based on years of our lives when my mother and I were often at war. The script made use of things I had written at that time, before I was able to put my rebelliousness and political stridency aside. After reading the script, she said to me, “I’m so sorry about the way you were portrayed.” I think I answered, “Well, we all came off terribly.” But the moment was not lost on me. A single sentence can be a bridge over currents of old history.

My father will leave, we all know that. There will be many people poring over his political career. There will be debates and discussions about his Presidency. But as a family, we will be elsewhere. We will walk past an empty room. We will be assaulted by the silence, the emptiness, and we will, I think, try hard to listen—to echoes, whispers, all those things that don’t vanish when a person dies. That is, if you believe in such things. My father did. And that might be his most important legacy for us—what lives on in the heart.

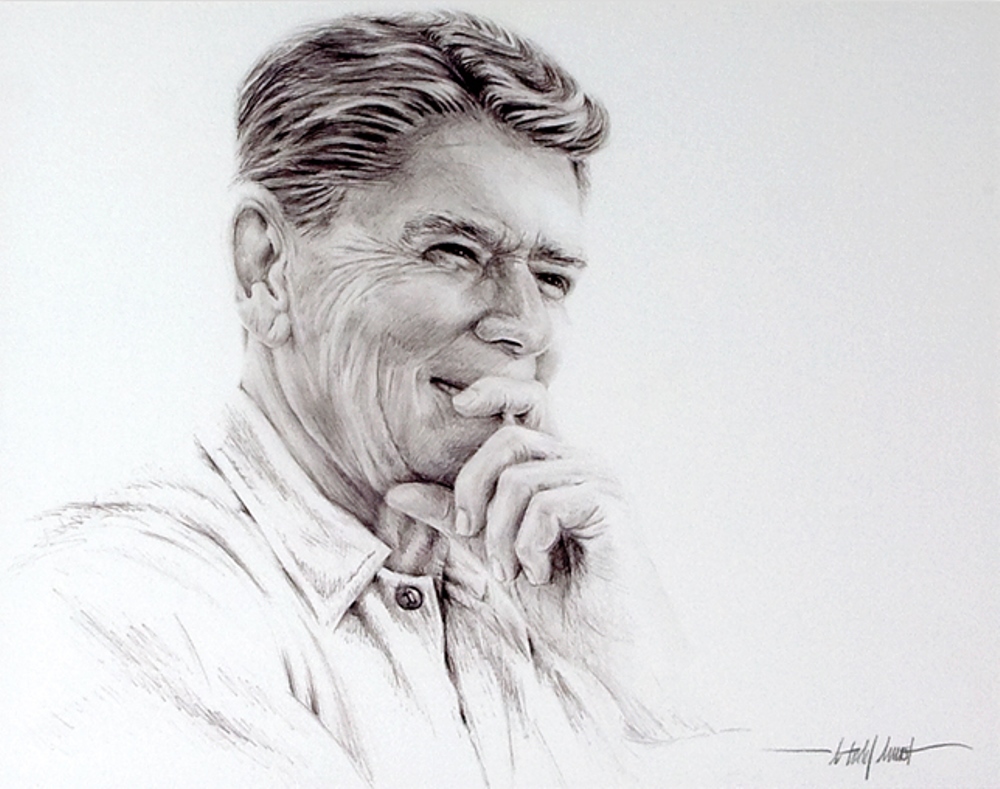

Portrait of Ronald Reagan by L. Todd Hurst, The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute.