Sometimes you have to go far away from home before you can understand why what you have might be too much.

Black clay de Oaxaca (Photo: Claudia Martínez)

Several years ago, I went to Mexico for ten days. It was safe to travel there then, and it’s a good thing it was—I was a single woman traveling alone, and at one point I found myself on a six-hour trek through the Sierra Madre mountains, from Oaxaca to Mexico City, on a second-class bus (yes, that’s what they called it) that took the mountain roads at such breakneck speeds, at times we came perilously close to tumbling right off the edge of the world and into the rocky ravine below. I remember thinking, This is it . . . I am going to die in the bowels of Mexico, and no one will ever know . . . but that’s a whole other story.

The point is, I was deep in the heart of Mexico—a foreign country with some parts so remote and poor, you have to wonder how people can even live there.

Oaxaca de Juárez, simply called Oaxaca, is a sleepy town nestled quietly in the foothills of the Sierra Madre del Sur. It is the capital of the State of Oaxaca, which borders the Pacific at the far southwest corner of Mexico. The city of Oaxaca, a six-hour mountainous drive inland from the coast, was my primary destination and about as far away from home as I had ever been before in terms of distance, economics, and culture.

Oaxaca has deep Zapotec roots. Its history predates the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521 by hundreds of years. Sitting high atop a mountain overlooking the city are the ruins of the ancient Zapotec capital, Monte Albán. For someone like me, who loves anything archaeological, it was a must-see.

Traditional window in Oaxaca

The city itself was charming. Cobblestone streets in the Centro Histórico district were gas lit and lined with Spanish colonial architecture in soft pastels and bright colors. Buildings had tall windows with wrought-iron gates or balconies. Fragrant bougainvillea spilled out over courtyard walls adding more splashes of vibrant color. Quaint little shops—selling barro negro pottery, alebrije figures, woven blankets, and painted metalwork—dotted the map. On every street corner was an historical church; and the 16th century church of Santo Domingo de Guzmán, with its gilded Baroque interior, was simply magnificent.

Most alluring was the lovely, tree-shaded Zócalo at the center of the city with its Victorian lacework gazebo, fountains, and pathways. Everyone gathered there—musicians, artisans, tourists, balloon vendors, native Zapotec and Mixtec selling their wares, Triqui women weaving blankets, and street children playing ball or peddling pencils and Chicklets for pennies. Best view of the scene was from the second-floor balcony of La Casa de la Abuela, a restaurant serving authentic Oaxacan food, including mole negro tamales, traditional caldo de gato (beef soup with vegetables and local corn), and roasted grasshopper. By nightfall, the square was ethereal under the gas lights and lively as a block party with marimba bands playing, Mezcal flowing, and the whole of Oaxaca invited.

It was easy to fall into the rhythm of the city. The people were warm, friendly, and helpful. The food was delicious. The climate was subtropical. The pace was slow. Oaxaca felt almost surreal and far-removed from mainstream Mexico . . . more authentic, more Indian, richer in history and culture. I felt at home there and at peace.

Returning to the USA, I experienced reverse culture shock. Almost immediately, I was not only keenly aware of the economic and other differences that were plainly obvious the minute I landed in Houston; but I was also rather appalled by what I perceived to be an almost obscene excess in American culture and, most specifically, in my own life.

My house, my yard, and all the other stuff I owned suddenly seemed to be way too much, too extravagant, and totally unnecessary for a single woman living alone. I didn’t need a big house with a full basement, three full baths, and rooms full of furniture. I didn’t need an acre of lawn to mow. I certainly didn’t need to work all week—with no time or energy for much else—just so I could afford a house that took me all weekend to clean. Where, I ask you, is the joy in that?

Our society measures success by the jobs we have, the amount of money we make, and the things we can buy with that money. To impress others and boost our own egos, we surround ourselves with stuff—big houses, new cars, cellphones, multiple TVs in multiple rooms, expensive toys, and gadgets galore. Many times, we can’t afford any of it comfortably—the houses are mortgaged, the cars are leased, and everything else is bought with revolving credit that never goes away. We live paycheck-to-paycheck just so we can hang on to the lifestyle we feel entitled to live . . . or we live above our means just to emulate a lifestyle we want . . . and in the process, we lose our grasp on what is truly important.

The things I owned were not enhancing the quality of my life.

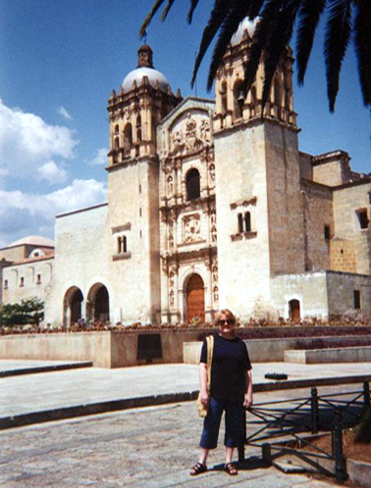

Street corner near the

Church of Santo Domingo de Guzmán

Oaxaca is one of the poorest states in Mexico. Indigenous people make up a large part of its population. Many of them are socially marginalized, living in extreme poverty in and around the city. It’s not unusual for whole families—parents and their adult children with spouses and children of their own—to share a house the size of my living room.

On the way to the ruins at Monte Albán, I saw ramshackle corrugated metal boxes clustered together on hillsides—the Oaxacan equivalent of American suburbia. Vendors on bicycles rode through town in the early-morning hours selling plastic jugs of safe drinking water. Men swept the city streets with straw brooms. Beggars were a common sight on church steps. Street children worked in the Zócalo in order to survive or help their families. My own up-close-and-personal experience came when a Triqui mother of five tearfully praised the heavens above and blessed me for giving her $20 for a $2 blanket. I was told that $20 was more money than she could hope to make in a month.

These things affected me deeply. In sharp contrast, I was living well, surpassing my basic needs, spending too much on my house and wasting precious time, energy, and freedom trying to maintain it. This is not to say I wanted to give up creature comforts and embrace a life of poverty; but I knew, for starters, that I would be perfectly content living in a little house with nothing better to do on weekends than tend my flower garden.

Life in Oaxaca had been simple and uncomplicated. I had been happy there . . . living in the moment . . . less concerned with where or how I lived than with the quality of my days. I crammed as much as I could into every one of them. I made each day matter. I wanted to feel the excitement and joy that come when you experience new things. I was living life to the fullest.

Me at the Church of Santo Domingo de Guzmán

Granted, I had been on vacation. Vacations have a way of suspending reality, and in the warm glow of nostalgia, memory is oftentimes selective. Still, what I remember most is the profound joy and peace I found in that foreign place. My trip had been a learning experience. It put things into perspective and showed me what mattered most.

It’s not so much the memories; but, rather, the feelings the memories invoke.

On the Zócalo in Oaxaca, I had laughed out loud and played ball with the street children. Friends, who saw the photo of me taken that night, said I never looked happier.