“Love settles within the circle, embracing it and thereby lasting forever, turning within itself.” —Luther Standing Bear, Oglala Sioux

A Sacred Symbol

The circle has always been an important symbol to the Native American. It represents the sun, the moon, the cycles of the seasons, and the cycle of life to death to rebirth.

in his own words

“Returning Home” by Aaron Paquette

You have noticed that everything an Indian does is in a circle, and that is because the power of the world always works in circles, and everything tries to be round.

In the old days all our power came to us from the sacred hoop of the nation; and so long as the hoop was unbroken, the people flourished. The flowering tree was the living center of the hoop, and the circle of the four quarters nourished it. The east gave peace and light, the south gave warmth, the west gave rain, and the north with its cold and mighty wind gave strength and endurance. This knowledge came to us from the outer world with our religion.

Everything the power of the world does is done in a circle. The sky is round, and I have heard that the Earth is round like a ball and so are all the stars. The wind, in its greatest power, whirls. Birds make their nests in circles, for theirs is the same religion as ours. The sun comes forth and goes down again in a circle. The moon does the same and both are round. Even the seasons form a great circle in their changing and always come back again to where they were.

The life of a man is a circle from childhood-to-childhood, and so it is in everything where power moves. Our tipis were round like the nests of birds, and these were always set in a circle, the nation’s hoop, a nest of many nests, where the Great Spirit meant for us to hatch our children.

Hopi “Man in Maze” labyrinth

Labyrinth Mandalas

Mandalas are a powerful symbol in Native American culture and tradition. They are often used during prayer, ceremonial blessings, vision quests, and other rituals.

Labyrinth mandalas represent birth, death, rebirth, and/or the transition from one world to the next.

They combine the imagery of the sacred circle with a maze (labyrinth) to create a meandering but purposeful path. The maze with its twists and turns is the difficult journey we all take toward finding deeper meaning in life.

Tracing the labyrinth with your finger is an easy way to practice mindful meditation.

The Man in the Maze labyrinth mandala was originally created by the Tohono O’Odham Nation of the Central Valley in Arizona. The man at the top of the maze depicts birth. By following the white pattern, beginning at the top, the figure goes through the maze encountering many turns and changes, as in life. As the journey continues, one acquires knowledge, strength, and understanding. Nearing the end of the maze, one retreats to a small corner of the pattern before reaching the dark center of death and eternal life. Here one repents, cleanses, reflects back on all the wisdom gained. Finally, pure and in harmony with the world, death and eternal life are accepted.

The Man in the Maze is a popular motif used today in hand woven baskets, potter, silverwork, art, and tattoos.

Dreamcatchers

The Ojibwe created the dreamcatcher, an item made to catch bad dreams and let good dreams pass through. They viewed dreaming as an important connection to the spirit world.

The Ojibwe created the dreamcatcher, an item made to catch bad dreams and let good dreams pass through. They viewed dreaming as an important connection to the spirit world.

Dreamcatchers are fashioned by tying sinew in a web around a circular frame of willow. They can include feathers and beads and are traditionally hung above children’s beds to catch any bad dreams or other harm that might be present.

Each part of a dreamcatcher has meaning. Its round shape represents the earth. Feathers act like ladders allowing good dreams to descend on the infant or adult who is sleeping. The web absorbs bad dreams at night and discharges them during the day.

According to Lakota legend: “Good dreams pass through the center hole to the sleeping person; bad dreams are trapped in the web, where they perish in the light of dawn.”

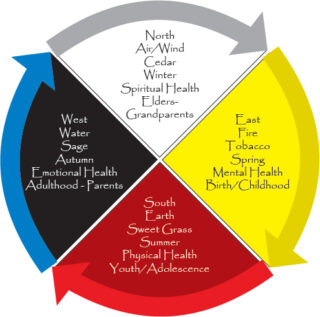

The Medicine Wheel

The Medicine Wheel, an ancient and powerful symbol of the never-ending cycle of life, is used by Native Americans for various spiritual and ritual purposes.

The ancient Bighorn Medicine Wheel, located in Bighorn National Forest near Sheridan, WY, is a national historical landmark and considered a sacred site by local Native Americans and New Age practitioners. The markings of the wheel align with solstice sunrise and sunset and the rising locations of the three brightest stars.

It is perhaps the location of the Bighorn Medicine Wheel that contributes so powerfully to a feeling of sacredness and agedness. Lying atop Medicine Mountain at nearly 10,000 feet, the weather is as wild as the towering crags and sheer cliffs that define the mountain. Sleet, rain, and snowstorms are common, even in July. Streaks of jagged lightning, deafening thunder, and wind scream past the rocky embattlements. These are the forces that confronted the people who came here, ages ago, to build a place of ceremony and worship.

The term “medicine wheel” was first coined by white men in the late 1800’s in reference to the Bighorn Medicine Wheel. Traditional medicine wheels, like the one at Bighorn, were stone structures constructed by Native Americans for various astronomical, ritual, healing, and teaching purposes. The wheels followed a basic pattern—a stone center surrounded by an outer ring of stones with lines of rocks, or “spokes,” radiating from the center.

Medicine wheels, or “sacred hoops,” are a symbol of harmony, balance, and peaceful interaction among all living beings on Earth. They represent the sacred cycle of life (birth, death, rebirth), its four cardinal directions (west, north, east, south), the elements (water, air, fire, earth), as well as connecting points for Mother Earth and Father Sky and the center point, representing ourselves and how we connect with all of these elements.

Each direction offers its own lessons, color, and animal spirit guide. The four animals commonly used for guides are the bear, buffalo, eagle, and wolf.

Each direction offers its own lessons, color, and animal spirit guide. The four animals commonly used for guides are the bear, buffalo, eagle, and wolf.

The shape of the cross symbolizes all directions. The circle represents the cycle of life from birth, youth, to elder, and death.

“The Indian observed that there were no straight lines in nature. The sun and the moon were round, and so was the earth. The rising and the setting of the sun was a circular motion. Birds built their nests in circles. The growth pattern of trees and rocks was circular. Many Indians lived in circular homes called tipis, and native communities were set up around a circle because the whole of nature expressed itself in circular patterns. Only the white man, it seemed, thought of everything in straight lines.” ―Kenneth Meadows

The Four Directions

Adapted from Lakota Life by Ron Zeilinger

The Lakota see the world as having Four Directions—east (Gi), and south (Okaga Ska), west (Sapa), and north (Luta). Each direction is accompanied by a specific color—yellow, red, black, and white, respectively.

East (Gi) – Yellow

East is a place of brightness, light, and clarity. It is the direction from which the sun comes. Light dawns in the morning and spreads over the earth. It is the beginning of a new day. It is also the beginning of understanding because light helps us see things as they really are. On a deeper level, east stands for the wisdom needed to help people live good lives. Traditional people rise in the morning to pray facing the dawn, asking for wisdom and understanding.

South (Okaga Ska) – Red

South is a place or door between the spirit world and the visible realm. Because the sun is at its highest in the southern sky, this direction stands for warmth and growing. The sun’s rays are powerful in drawing life from the earth. It is said the life of all things comes from the south. Also, warm and pleasant winds come from the south. When people pass into the spirit world, they travel the Milky Way’s path back to the south, returning from where they came.

West (Sapa) – Black

To the west, the sun sets and the day ends. Thus, the west is considered a place of darkness. It signifies solitude or meditation and crossing into the spiritual realm. The thunderbeings (wakinyan) reside in the west, sending thunder and rain from its direction. Thus, the west is also the source of water—rain, lakes, streams, and rivers.

North (Luta) – White

North is a place of spiritual renewal. It represents the trials people must endure and the cleansing they undergo. The north brings cold, harsh winds and the winter season. They cause the leaves to fall and the earth to rest under a blanket of snow. If you have the ability to face the north winds, like buffalo heading into a storm, you have learned to overcome hardships and discomfort.

As with many Native American beliefs and traditions, specific details regarding colors associated with directions are interpreted differently by different tribes. Some tribes vary the colors, animal representations, and meaning; but one thing is sure is—the Spirits of the Four Directions are powerful and waiting to be called upon for direction and help.

By walking the wheel of the four directions in this life you can experience the many birth-and-death cycles that lead to former aspects of yourself. It is a natural way to learn lessons and gain wisdom. When we gain wisdom, we can help others walk the circle to spiritual renewal.

The Seven Circles for Living Well

When Native American wellness teachers and husband-wife duo Chelsey Luger and Thosh Collins founded their Indigenous wellness initiative, Well for Culture, they extended an invitation to all to honor their whole self through Native wellness philosophies and practices. Drawing from traditions spanning multiple tribes, they developed the Seven Circles—a holistic model for modern living rooted in timeless teachings from their ancestors.

The Seven Circles are interconnected to keep all aspects of life in balance, functioning in harmony with one another. Their book, “The Seven Circles: Indigenous Teachings for Living Well,” offers great insight into Indigenous wisdom for cultivating wellness without appropriating medicines, rituals or traditions from other cultures.

“The Seven Circles: Indigenous Teachings for Living Well” by Chelsey Luger and Thosh Collins, 2022

Yigaquu osaniyu adanvto adadoligi nigohilvi nasquv utloyasdi nihi

(May the Great Spirit’s blessings always be with you)

Man In The Maze Bronze Sculpture Allegory by James Muir.

Medicine wheel garden photo: “Making A Medicine Wheel Garden” by Ginny Shannon, Exeter Area Garden Club.

“Medicine Wheel” artwork/Source: Adam Garcia.

“Medicine Wheel of the Four Directions” by artist Jodi Bergsma.