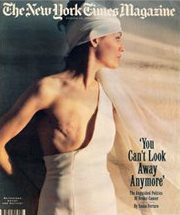

I was a little hesitant getting on the subway that Sunday morning, the day that the New York Times magazine ran my portrait on its front cover.

As an artist, I welcomed having my work so prominently exposed—the magazine has a circulation of almost two million—but until that morning I hadn’t thought much about the responses the photograph might provoke. I especially felt uneasy about how my father might react. My mother died from breast cancer 23 years ago, and when I was diagnosed with the disease and had a mastectomy in 1991, he took the news so badly that I had to bar him from visiting me until he could collect himself.

“I hope they’re going to show you looking good and not sick,” he had said when I told him about the upcoming cover.

“No . . . I . . . er . . . look really beautiful,” I said. “but it is an honest photograph.”

Before landing the Times cover, I’d been frustrated over not finding a home for photographs like this one, which I had been working on ever since I learned I had cancer. Although many small leftist magazines had published me, it was Middle America I wanted to reach. After all, breast cancer is not a leftist disease. It afflicts women of all political persuasions, all ages and colors.

Actually, my breasts and my body have long been a focus of my work. I was a lingerie model in the seventies and in the eighties I photographed my nude figure among abandoned buildings. After my mastectomy, I was not only afraid for my life; I was upset about loosing my “material,” about becoming asymmetrical and unaesthetic. My “breastless” photographs became a challenge, a way to prove to myself that I could still use my body to make beautiful pictures. When I succeeded, I thought: “now I can make art out of anything.”

At this time I also became involved in the fight against breast cancer; it was at a rally that Susan Ferraro, the author of the Times cover story on breast cancer activism, saw one of my images.

On my subway car the morning that the photograph appeared, I noticed a woman who was thoroughly engaged in the Ferraro article. I had to ask: “What do you think about the Times putting that picture on the cover?”

“That’s you?” she asked, and pulled out a pen, asking me to sign her copy. “It’s great. Just where it belongs.”

I got off the train reassured, believing that all was well.

But by Monday morning my phone was ringing off the hook. I was besieged by television networks, radio stations, newspapers across the nation, magazines all over the world.

Still, it wasn’t until I witnessed the TV coverage—which captured people’s candid responses to the cover—and read through the 100 letters that the Times had received within days, that I fully understood the extent of the reaction. While much of what people had to say was extremely positive, I certainly did not please everyone as much as I had the woman on the subway.

“It’s embarrassing,” a man told a local TV news reporter.

“Disgraceful,” said a young woman. “The New York Times should be sued.”

I replied to these remarks in a television interview a few nights later, stating that embarrassed is something I feel when I do something stupid. Disgraceful is what I call it when someone hurts another person by being dishonest or deceptive. Dishonest is one thing my photograph is not.

Nearly all of the TV commentary claimed that people were accusing me of exploitation. Exploitation of what? It is my body that is displayed in the photograph, not anyone else’s. My photographs are not created with the expectation of financial gain—for over two years I have made almost no money from my work, What else could I be exploiting? Cancer?

I cared most about how other women who had had mastectomies felt about the cover. Had I invaded their privacy? Or had I opened up another perspective for them?

Most of these women, judging by their letters to the Times, were full of praise. “Thank-you for the cover story on breast cancer. It was like finding a fellow human on the backside of the moon,” said one. “I am going to frame that picture and hang it here in my office.” Another wrote she was initially shocked but conceded that the photo was “a good idea. The squeaky wheel does get the grease.”

The negative responses, which I found disheartening, fell into two categories. The first group of women spoke of feeling that their privacy had been violated—after seeing my mastectomy scar, the world would know what they really looked like. They said that the ability to see themselves as “normal” was essential to their self-esteem, and they accused me and the Times of having run the photo only for shock value. The other group worried that the photograph would prevent women from getting their breasts checked or from going for mammograms out of a fear that they would end up with a chest like mine.

Are women that vain? I refuse to believe that the majority of us value our lives less than our breasts. That we would rather live in fear or get sick and die than take simple preventative measures.

I have always adhered to the philosophy that one should speak and show the truth, because knowledge leads to free will, to choice. If we keep quiet about what breast cancer does to women’s bodies, if we refuse to accept women’s bodies in whatever condition they are in, we are doing a disservice to womankind.

Why is it “newsworthy” to put a child who has been maimed in the Bosnian war on the cover of Newsweek, but “exploitation” to show a woman with a mastectomy?

In publishing my photograph, my intention was never to harm or embarrass women who, like me, have gone through the painful and humiliating ordeal of mastectomy. My picture was about the choice made by me and many other women: We decided not to subject ourselves to any more reconstructive surgery, with all its risks, not to go through any more deceptions about our appearance and the risks to well-being that they can create. As actress Jill Ireland, who died of breast cancer in 1990, reportedly said, a prosthesis benefits other people, not the woman who has had the mastectomy—”It allows them to forget what happened to me.”

I hope that my image will convey the idea that a woman with one breast or no breasts is entitled to be looked at and approved of. My message is: “Don’t wait for society to accept you. Have courage to face yourself—the whole package. You become the role model and society will follow.”

And as a woman who had a mastectomy put it in her letter to the Times: “Fantastic! A cover girl who looks like me!”